Posted by Aquatic Veterinary Specialist on 7th May 2025

How to Treat and Prevent Velvet in Fish (Gold Dust Disease)

How to Treat and Prevent Velvet in Fish

Velvet disease – also known as gold dust disease or rust disease – is a highly contagious parasitic illness that affects both freshwater and saltwater aquarium fish. It is caused by tiny dinoflagellate parasites (species of Piscinoodinium in freshwater and Amyloodinium in marine environments) that attach to a fish's skin and gills. This disease is extremely dangerous because it can spread rapidly and quickly kill fish if not identified and treated promptly. In this article, we will explain what velvet disease is and why it’s harmful, outline its causes and life cycle, describe early and advanced signs of velvet in fish, and provide a comprehensive guide on how to treat velvet in fish and prevent it from reoccurring. We will also discuss the role of fish antibiotics for velvet in addressing secondary infections. By the end, you’ll know the best strategies for velvet fish disease treatment and keeping your aquarium healthy.

What is Velvet Disease?

Velvet disease is a parasitic infection in fish caused by a protozoan-like dinoflagellate. In freshwater fish, the culprit is usually Piscinoodinium pillulare (formerly Oodinium pilularis or Oodinium limneticum), while in saltwater fish it’s Amyloodinium ocellatum. Despite involving different parasite species, the disease presents very similarly in both freshwater and marine fish. A fish with velvet will have a dusty, yellow-gold or rust-colored film on its body, which gives the disease its “gold dust” name.

This parasite is particularly insidious because it feeds on the fish’s skin cells and gill tissue, causing irritation, tissue damage, and impaired breathing. A velvet outbreak can affect nearly all fish in an aquarium once the parasite is introduced. Young fish (like fry) and species such as bettas, danios, goldfish, and killifish are known to be especially susceptible. If left untreated, velvet disease can lead to organ failure, suffocation, and death of the fish in a matter of days.

Causes of Velvet in Fish

Velvet disease does not arise spontaneously – it requires the presence of the velvet parasite in the aquarium. Common causes and contributing factors include:

-

Introducing Infected Fish or Water: The most frequent cause is adding a new fish or water from an infected tank without proper quarantine. The parasite can hitchhike on new fish, plants, or even live food. Many pet store fish may carry velvet parasites in a dormant stage, only to show symptoms later.

-

Incomplete Quarantine Procedures: Skipping or shortening quarantine is a major risk factor. Experts recommend isolating new fish in a separate tank for 4–6 weeks to monitor for diseases like velvet before introducing them to your main display tank.

-

Poor Water Quality: Elevated ammonia, nitrite, or nitrate levels, improper pH, or high organic waste can stress fish and weaken their immune systems. Parasites like velvet often exploit stressed fish; in fact, Piscinoodinium is present in many aquariums but only becomes problematic when fish are stressed by poor water conditions or temperature fluctuations.

-

Temperature and Environmental Stress: Sudden changes in temperature or prolonged low temperatures can predispose fish to velvet. Likewise, overcrowding, aggressive tankmates, or inadequate diet can stress fish and make them more vulnerable to an outbreak.

-

Carrier Fish and Dormant Parasites: Sometimes a fish can carry a low-level infection with no obvious symptoms (the parasite can be endemic in a tank). When that fish or the tank undergoes stress, the parasites can multiply rapidly and manifest as a full-blown velvet disease outbreak. There are even rare reports of velvet cysts coming in via frozen or live foods, remaining dormant until conditions favor their growth.

By understanding these causes, aquarists can take precautions (like quarantining new additions and maintaining excellent water quality) to greatly reduce the risk of velvet disease entering their aquarium.

Symptoms of Velvet Disease in Fish

Recognizing the early signs of velvet in fish is crucial for timely treatment. Early detection can mean the difference between saving your fish and a tank-wide loss. Velvet disease symptoms can be subtle at first, but they quickly escalate as the parasites multiply. Below, we outline both early and advanced symptoms of velvet (gold dust disease) to help you identify it in your fish.

Velvet disease often appears as a fine yellow or rusty gold dusting on the fish’s skin, as seen on the head and body of this Oscar fish. This velvety film may be difficult to spot under normal lighting, but it becomes evident when you shine a flashlight on the fish in a dark room. Infected fish will frequently show clamped fins (holding their fins tightly against the body) and flash or scrape themselves against hard objects in the tank in an attempt to dislodge the parasites. The gills are usually attacked by the parasite, leading to labored, rapid breathing (you may see the fish gasping or “gilling” quickly) as the fish struggles to get enough oxygen.

Early symptoms of velvet disease include:

-

Fine gold, yellow, or rust-colored sheen on skin: Infected fish develop a dust-like coating that can make them look as if they were sprinkled with powder. It’s often easiest to observe on the fins or gill area, and using a flashlight can help reveal this coating.

-

Clamped fins: The fish holds its dorsal and pectoral fins close to its body, indicating discomfort.

-

“Flashing” or Rubbing: Infected fish will scratch themselves against tank decorations, substrate, or any hard surface. This behavior (called flashing) is due to skin irritation and itching caused by the parasites burrowing into the slime coat.

-

Loss of Appetite: In the early stages, fish may begin eating less or spit out food due to stress and discomfort.

-

Lethargy and Hiding: You may notice your fish becoming less active, hovering near the bottom or hiding more than usual as the infection takes hold.

-

Color Dullness: Some fish lose vibrancy in their coloration and may appear pale or dusty.

As the disease progresses, advanced symptoms become evident:

-

Pronounced “Velvet” Coating: The golden or brownish film on the fish becomes thicker and more widespread. By now it’s usually very noticeable on the body and fins, almost resembling a velvet-textured layer.

-

Rapid, Gasping Breathing: The parasites heavily infest the gills in advanced stages, severely hampering the fish’s ability to breathe. Fish may gasp at the surface or display flared gills with rapid gill movement. This is a sign of significant gill damage.

-

Severe Lethargy: The fish becomes extremely weak and may lie on the substrate or float listlessly. It may show little response to stimuli at this stage.

-

Skin Peeling or Shedding: A critical symptom of advanced velvet is the peeling off of the fish’s slime coat and outer skin layer, often seen as whitish stringy mucus or flaking skin sloughing off. This occurs as the parasites destroy the skin cells, and the fish’s body attempts to shed the irritated tissue.

-

Fin Damage: Fins might become frayed or begin to disintegrate, either from the parasite’s attack or due to secondary bacterial infections taking hold on the damaged tissue.

-

Opacity or Cloudy Eyes: In some cases, the eyes may get cloudy due to mucus or infection when velvet is severe.

-

Death: Unfortunately, if velvet disease reaches an advanced stage without intervention, it often results in the death of the fish. Mortality is high because by this point the fish may be suffocating due to gill damage and has lost its protective skin barrier.

Important: Velvet can kill very quickly, sometimes within 48–72 hours of obvious symptoms, especially in small or delicate fish. Always act immediately if you suspect velvet disease – early treatment is far more effective and gives your fish a fighting chance.

Life Cycle of Velvet Parasites

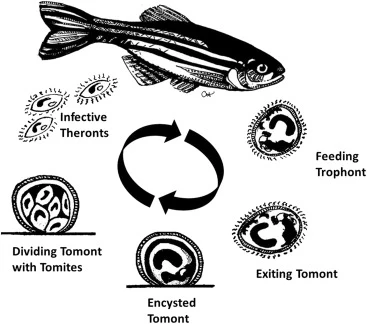

Understanding the life cycle of velvet parasites is key to effective treatment. The parasite (Piscinoodinium/Amyloodinium) has a multi-stage life cycle, and not all stages can be killed by medications. Here’s an overview of the cycle and why it matters for treating velvet:

-

Tomont (Cyst) Stage: The adult parasite (sometimes called a trophont when feeding on the fish) eventually drops off the fish and encysts, usually attaching to the aquarium substrate or surfaces. Inside this cyst (called a tomont), the parasite divides rapidly into dozens or even hundreds of tiny cells. One tomont can produce up to 256 new parasites (tomites). This cyst phase can happen on the tank bottom or any surface, and during this stage the parasite is protected by a hard outer shell – medications cannot penetrate the cyst.

-

Dinospore (Free-Swimming) Stage: The cyst eventually bursts, releasing the motile young parasites called dinospores (sometimes also referred to as tomites). These free-swimming dinospores swim through the water column in search of a fish host. At this stage they even use photosynthesis to gain energy, which is why velvet parasites thrive with light. The free-swimming stage is the only point where the parasite is vulnerable to treatment – medications like copper or other treatments can kill the parasite in this stage.

-

Attachment (Trophont) Stage: If a dinospore finds a fish within its limited time (usually within 24–48 hours of release), it attaches to the fish’s skin or gills and develops into a feeding stage known as a trophont. The parasite burrows into the fish’s slime coat and epithelial tissue, feeding on the cells and causing the characteristic velvet dusting on the fish. In this stage, the parasite is somewhat protected from chemicals by being under the fish’s mucus layer, so medications are less effective against attached trophonts. The trophont grows over a few days (roughly 2–3 days to mature) while feeding.

-

Reproduction and Restart: After feeding and maturing on the fish, the trophont drops off and encysts as a tomont again. The cycle then repeats, with a new generation of parasites ready to infect more fish.

Why this matters: Because of this life cycle, a one-time treatment will not eradicate velvet. You must treat for an extended period (often 10–14 days, or multiple cycles of treatment) to ensure you catch each new wave of dinospores as they emerge. Any trophonts that are on the fish or tomonts encysted in the tank will survive initial treatment, so medication must remain in the water long enough to kill them once they become free-swimming. Additionally, speeding up the life cycle can help (for instance, by raising the water temperature a few degrees, you can accelerate the parasite’s timeline so that dinospores are released sooner to be killed). This life cycle also explains why turning off aquarium lights can aid treatment: since the parasites rely on light for energy during the free-swimming stage, keeping the tank dark can slow their growth and reproduction.

Treatment Guide: How to Treat Velvet Fish Disease

When dealing with velvet, time is of the essence. Because this disease is highly contagious and often advanced by the time it’s noticed, you should begin treatment immediately once you suspect velvet. The following is a step-by-step velvet fish disease treatment guide:

-

Isolate Infected Fish (Quarantine): If possible, move the affected fish to a hospital tank for treatment. Isolation helps in two ways: it prevents the disease from spreading to other healthy fish, and it allows you to treat in a smaller volume of water (which can be easier and safer when dosing medications). In a reef tank or planted tank, removal is often necessary because treatments like copper can harm invertebrates and plants. However, note that if one fish in a community tank shows velvet, the entire tank is likely infected. You may need to treat the main tank (especially for freshwater setups) or leave it fishless (fallow) for a period while treating the fish elsewhere. Always use separate nets/equipment for sick fish to avoid cross-contamination.

-

Perform a Water Change and Tank Cleaning: Before medicating, do a 30% water change in the affected aquarium (or hospital tank) and vacuum the substrate thoroughly. This helps remove some of the tomonts (cysts) and dinospores in the water, reducing the parasite load. Clean the filter gently and remove any debris where parasites might be lurking. Good water quality also boosts the fish’s ability to fight the disease.

-

Turn Off the Lights (Blackout): Velvet parasites derive energy from light via photosynthesis during their free-swimming stage. Keeping the tank completely dark for several days will hinder the parasite’s growth and reproduction. Drape a towel over the quarantine tank or turn off aquarium lights and cover the tank to block out ambient light. Maintain this blackout for at least 3–7 days while other treatments are ongoing. (Fish can handle a week of darkness, but if you have live plants, they may suffer – another reason to treat in a separate tank if possible.)

-

Increase Water Temperature (Gradually): If your fish species can tolerate it, slowly raise the aquarium temperature by a few degrees (up to around 82–86°F or ~28–30°C, depending on tolerance). Warmer water speeds up the parasite’s life cycle, causing the trophonts to mature and drop off faster, which in turn makes the dinospores vulnerable to treatment sooner. Important: Increase temperature gradually (no more than 1–2°F per hour) to avoid shocking the fish, and ensure you have adequate aeration (warmer water holds less oxygen). If your fish are cold-water species or cannot handle higher temps, skip this step.

-

Add Aquarium Salt: For freshwater fish, adding aquarium salt can help alleviate velvet. Salt interferes with the parasite’s reproduction and also aids the fish in restoring its slime coat. Dose according to instructions (commonly, 1 to 3 teaspoons of salt per gallon for a therapeutic bath in a separate container, or a lower dosage in the tank if fish are salt-sensitive). Note: Some freshwater fish (like scaleless fish or certain catfish) and all marine tanks (already saltwater) require caution with salt treatments. Salt alone may not cure velvet, but it is believed to mitigate the reproduction of velvet and provide some relief. In fact, a concentrated salt dip (e.g., placing the fish in a separate bucket with a strong salt solution for 3-5 minutes) can kill some external parasites and is often cited as one of the safest treatments for freshwater velvet.

-

Use an Effective Anti-Parasitic Medication: Medicating the fish and water is the cornerstone of velvet treatment. The most effective medications for velvet are copper-based treatments. Chelated copper solutions (like copper sulfate, e.g., Mardel Coppersafe®) are widely recommended. Copper medication at the proper concentration will kill the free-swimming dinospores. Follow the product instructions carefully – usually, you’ll maintain the copper treatment for about 10–14 days. Use a copper test kit if possible to ensure the therapeutic level is reached and maintained (too little won’t kill the parasite, too much can harm fish). In saltwater, copper is the go-to cure for marine velvet. In addition to copper, other treatments include:

-

Formalin Baths or Baths with Acriflavine: Short-term dips in solutions containing formalin (a formaldehyde solution) can help kill parasites on the fish’s surface. Acriflavine is another chemical that can be used (often available in antiparasitic fish medications) – it’s effective against protozoans and also has some antibacterial properties. Always use these chemicals in a separate bath or hospital tank, as they can be harsh and will harm biological filtration in the main tank.

-

Methylene Blue or Malachite Green: These are traditional parasite treatments. Methylene blue can aid in relieving stress on the fish’s gills and also treats some external protozoans. Malachite green (often combined with formalin in meds like “Quick Cure”) can be effective against velvet as well. Be cautious as these can stain silicone and are toxic to plants/inverts.

-

Hydrogen Peroxide Dips: In some cases, a brief bath (several minutes) in diluted hydrogen peroxide has been used to combat external parasites (this is more experimental and must be done carefully to avoid harming the fish).

-

Combination Medications: Some commercial treatments (e.g., Ruby Reef Rally or API General Cure, etc.) contain blends of chemicals like acriflavine, formalin, and others, which can tackle velvet and prevent secondary infections simultaneously.

Regardless of the medication you choose, remove any activated carbon or chemical filtration from the filter before dosing, as carbon will absorb medications out of the water. Continue treatment for the full recommended duration even if the fish’s visible symptoms improve sooner – stopping early can allow a resurgence of the parasite from any remaining cysts.

-

-

Improve Oxygenation and Water Circulation: Because velvet attacks the gills, fish often struggle to breathe. It’s crucial to increase oxygen levels in the water during treatment. Add an air stone or additional aeration, and consider pointing a filter return or wavemaker toward the surface to maximize gas exchange. This ensures the weakened fish get enough oxygen and also helps them handle higher temperatures and medication, which can lower oxygen content in water. Good circulation also distributes medication evenly.

-

Monitor Water Quality and Parameters: Throughout treatment, keep a close eye on ammonia, nitrite, and nitrate levels. Some medications (like formalin or antibiotic use) can impact the beneficial bacteria in your filter, leading to spikes in ammonia. Perform small water changes if needed (re-dosing medication for the water removed) to keep water quality high. Stable, clean water reduces stress and helps the fish’s immune system fight off the disease.

-

Secondary Infection Control: In severe cases of velvet, the damage to a fish’s skin and gills can invite secondary infections (bacterial or fungal). If you notice open sores, red patches, fin rot, or other signs of infection on your fish, consider treating with a broad-spectrum antibiotic safe for fish (more on this in the next section). Using an anti-bacterial medication to control possible secondary infection is often necessary in addition to parasite treatment. Many aquarists will proactively add an antibiotic in a hospital tank when treating velvet to preempt any bacterial issues while the fish is vulnerable. Just be sure not to mix medications that are incompatible (check labels or consult a vet; for example, copper and antibiotics usually can be used together, but avoid mixing multiple parasite meds simultaneously).

-

Complete the Full Treatment Course: Do not stop treatment as soon as fish look better. Velvet can hide in cyst form. Continue medicating for at least 10 days (for copper treatments, often 10–14 days is recommended), or repeat dosage according to product directions (some require dosing daily or every few days). It can be helpful to slightly prolong treatment (a few extra days) to ensure all parasite life cycle stages have been eradicated. After treatment, run fresh activated carbon in the filter to remove any residual medication from the water, and perform a series of partial water changes over a couple of days to return the tank to normal conditions.

-

Recovery and Observation: Keep the recovering fish in quarantine for a while to regain strength. Offer high-quality, easy-to-eat foods (e.g., soaked pellets or frozen foods) to help them recover weight and nutrition. Observe closely for any reemergence of symptoms. Only return fish to the display tank once you are confident velvet is gone and the fish are healthy. If the main tank was left without fish, ensure it remained fishless for long enough to starve out any remaining parasites (with velvet, a fishless period of 2–3 weeks at tropical temperatures can be effective since dinospores die without a host in about 2 days, but some recommend up to a month to be safe).

This comprehensive approach – isolation, environmental modifications, proper medication, and supportive care – gives your fish the best chance to survive a velvet outbreak. Always remember to handle chemicals carefully, follow instructions, and never overdose treatments in a panic. When in doubt, consult with a veterinarian specialized in fish or experienced aquarists for guidance.

Fish Antibiotics for Velvet Disease (Secondary Infections)

Velvet itself is caused by a parasite, so antibiotics do not kill the velvet organism. However, the damage caused by velvet can lead to secondary bacterial infections in your fish (for example, bacteria can infect the raw areas of skin or gills after the parasite has caused tissue damage). In these cases, treating your fish with antibiotics can be crucial to healing and preventing further complications. In fact, sources note that the use of an antibacterial drug to control possible secondary infection is necessary when treating velvet.

Fish antibiotics are formulations of common antibiotics packaged for aquarium use (often the same medications used in humans, but sold for fish and usually available without a prescription). They can help combat opportunistic bacteria like Aeromonas, Pseudomonas, and Flavobacterium that cause issues like fin rot, ulcers, or gill infections in stressed fish.

Some commonly used fish antibiotics for velvet-related infections include:

-

Fish Amoxicillin – A broad-spectrum penicillin-type antibiotic effective against many gram-positive and some gram-negative bacteria. Often used for bacterial sores or fin rot in fish. (Available in capsules that can be dissolved in the aquarium water.)

-

Fish Cephalexin – A cephalosporin antibiotic that is effective against a variety of bacterial fish diseases. Useful for treating wounds or systemic infections in fish.

-

Fish Penicillin – Another penicillin-class antibiotic for fish, effective especially on gram-positive bacterial infections. It can help prevent minor secondary infections from becoming serious.

-

Fish Ciprofloxacin – A fluoroquinolone antibiotic that treats gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. Ciprofloxacin is potent and used for serious bacterial infections in fish (like columnaris or septicemia) when other antibiotics might fail.

-

Fish Metronidazole – An antiparasitic and antibiotic, metronidazole is commonly used for internal protozoan infections (like Hexamita) and anaerobic bacterial infections. While it won’t kill velvet parasites on the fish’s skin, it could be used if velvet has caused internal infections or to help with certain gut parasites that might co-occur.

-

Fish Clindamycin – A lincosamide antibiotic effective mostly against gram-positive bacteria and some anaerobes. It’s sometimes used for fish with abscesses or infected wounds.

-

Fish Azithromycin – A macrolide antibiotic that can treat a broad range of infections, including some difficult ones like mycobacterial infections (fish tuberculosis) in early stages, or general infections not responsive to other meds.

-

Fish Doxycycline – A tetracycline-class broad-spectrum antibiotic. Doxycycline is used for treating fin rot, mouth rot, and other bacterial issues in fish. It’s also somewhat effective against certain parasites like gill flukes due to its antiparasitic properties.

-

Fish Sulfamethoxazole – A sulfa antibiotic (often combined with trimethoprim as SMZ-TMP). It’s effective against a range of bacterial infections and is useful for fish due to its broad action.

-

Fish Fluconazole – Fluconazole is actually an antifungal medication, not an antibiotic. It’s included here because fungal infections can also set in on damaged tissue. Fluconazole can treat fungal issues like cotton wool disease or fungus on wounds that might occur after the stress of a velvet outbreak.

When using fish antibiotics, always follow the recommended dosage and treatment duration on the product. It’s usually a 10-14 day course for antibiotics to fully knock out an infection. Remove activated carbon from filters during treatment (so it doesn’t suck out the medication), and monitor water quality – antibiotics can sometimes harm beneficial bacteria in the biofilter, potentially causing ammonia spikes. If possible, treat bacterial infections in a separate hospital tank to avoid impacting the main tank’s biofilter.

Lastly, avoid using antibiotics “just in case” if you don’t suspect a secondary infection, as overuse can lead to resistant bacteria. But if your fish have visible sores, red streaks, fungus, or other complications from velvet, these fish antibiotics can be literal lifesavers. They are available for aquarium use without prescription, making them accessible when you need to act quickly.

Prevention Strategies for Velvet Disease

Preventing velvet disease is far better than dealing with an outbreak. By taking the following preventive measures, you can protect your aquarium fish from velvet (and other diseases):

-

Quarantine New Arrivals: Always quarantine new fish, invertebrates, or even plants in a separate tank for at least 2–4 weeks (4-6 weeks is ideal). Observe them closely during this period for any signs of illness. Treat proactively if any symptoms appear. This quarantine tank can be kept with low salinity or a small dose of copper as a preventative measure (especially for marine fish) to ensure no parasites make it through. Never introduce new fish directly into your display aquarium without quarantine, no matter how healthy they look at the store.

-

Maintain Excellent Water Quality: Stress is a huge factor in disease outbreaks. Keep your tank water pristine – regular water changes (e.g., 25% weekly), proper filtration, and monitoring of ammonia/nitrite (which should always be zero) and nitrate levels will keep fish healthy and stress-free. Stable temperature and pH, appropriate for your fish, are also important. High water quality and stable parameters boost your fishes’ immune systems, making them less likely to succumb to a few parasite cells.

-

Avoid Temperature Fluctuations: Use a reliable heater (and maybe a backup heater) to prevent drops in temperature, and avoid placing the tank where sunlight or drafts can cause swings. If you need to adjust temperature, do it gradually. Many parasites, including velvet, can exploit fish that are chilled or stressed by changing temps.

-

Reduce Stress: Provide a suitable environment for your fish – appropriate tank size, hiding spots, and compatible tankmates. Overcrowding or aggressive tankmates can stress fish, suppressing their immune response. A calm, enriched environment means less stress and a lower chance for diseases to take hold.

-

Do Not Cross-Contaminate: Parasites can hitchhike on equipment. Have dedicated nets, siphons, and tools for each tank, or sterilize equipment (for example, using a mild bleach solution or very hot water) between uses in different tanks. If you maintain multiple aquariums, be mindful when moving decorations or equipment from one to another. This can prevent transferring any possible Oodinium or Amyloodinium cysts.

-

Use UV Sterilization: Consider using a UV sterilizer in your aquarium filter system. UV light can kill free-swimming pathogens like velvet dinospores. While not a guarantee against disease, UV can reduce the concentration of parasites in the water and is a good preventative tool, especially in marine systems prone to velvet.

-

Preventive Treatments: Some aquarists proactively use low levels of aquarium salt or medications in their tanks to ward off parasites. For example, maintaining a therapeutic low level of copper in a fish-only marine tank (such as using products like Coppersafe® at a very low maintenance dose) can keep velvet at bay. Likewise, a small amount of salt in a freshwater tank (if the fish tolerate it) can help deter parasites. These measures are optional and must be done carefully to avoid harming fish or plants, but in systems with frequent new additions (like retail store tanks), they can be effective.

-

Observe and Act Quickly: Even with all precautions, always keep a close eye on your fish. Early signs of velvet (like subtle gold dusting or scratching behavior) should be acted upon immediately. If you catch velvet in its very first stages, you might be able to treat just an individual in quarantine and save the rest from exposure. Getting to know your fishes’ normal appearance and behavior will help you spot when something is “off.”

-

Healthy Diet and Immune Support: Feed your fish a high-quality, varied diet to keep them in top condition. A well-nourished fish can better fight off infections. Some foods or additives (like garlic extracts or vitamin supplements) are believed to boost fish immunity or make them less appetizing to parasites, though results can vary. At the very least, good nutrition will improve recovery and resistance.

By implementing these prevention strategies – quarantine protocols, water maintenance, stress reduction, and vigilance – you greatly minimize the chance of velvet disease ever appearing in your aquarium. Preventing the disease not only protects your fish but also saves you the hardship of having to treat a full-blown outbreak.

Conclusion

Velvet disease is one of the more dreaded aquarium fish illnesses due to how fast it can strike and spread. Both freshwater and saltwater fish are at risk from this “gold dust” parasite. The key takeaways for every aquarist are: remain vigilant for symptoms, act quickly with appropriate velvet fish disease treatment (isolation, darkness, heat, salt, medication, and supportive care), and above all, practice good prevention by quarantining new fish and maintaining a low-stress, clean environment. With prompt action and the right treatment plan, velvet can be defeated, and your fish can recover. And by following the prevention tips, you can keep this parasite out of your aquarium for good, ensuring your aquatic pets stay healthy and velvet-free.

Remember, when in doubt, consult with a fish vet or aquatic specialist – but armed with the knowledge from this guide, you are well prepared to both treat and prevent velvet in fish, keeping your aquarium thriving. Happy fishkeeping!

Sources:

-

Fritz Aquatics – Velvet (Oödinium) description and treatment

-

The Spruce Pets – Velvet in Aquarium Fish (Dr. Jessie Sanders, DVM)

-

Arka Biotech – Guide on Oodinium (Velvet) Disease

-

FishBase – Velvet Disease summary (Bassleer, 1997)

-

Miami University Microbiology Dept. – Oodinium Life Cycle